Here I will describe some of my scientific research and interests, and in the text I provide hyperlinks to my main publications. For an explanation of the main concepts, such as what is cosmology or a galaxy survey, it might be useful to check the blog. For a complete list of publications, grouped by my level of involvement in them, please see my CV. If you have any inquiries, please feel free to contact me.

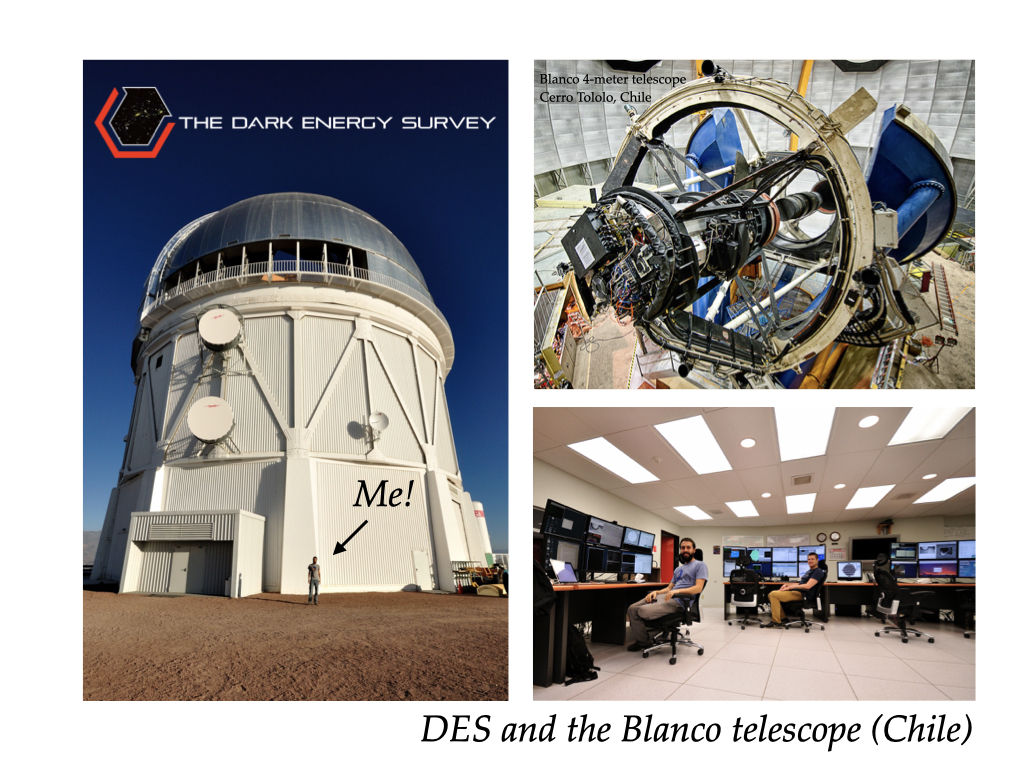

I am a physicist working at the intersection between astronomical data, theory and statistics. I am interested in cosmology as probed by the large-scale structure of the Universe and its weak gravitational lensing effect, and hence I work with data from galaxy surveys. During my career, I have made several contributions to the success of imaging surveys as a new key cosmological probe, focusing on overcoming their limitations and reinforcing their strengths, and I have worked with data from the Dark Energy Survey (DES). DES is an international, collaborative ongoing effort to image and analyze hundreds of millions of galaxies by using a dedicated extremely sensitive 570 Mega-pixel camera (DECam) mounted on the Blanco 4-meter telescope in Chile.

I have been a member of the DES Collaboration since 2013, and I hold builder status and act as the co-lead of the Redshifts Working Group and member of the DES Science Committee. In particular, I have been the lead author of a number of key DES publications, such as the first photometric redshift analysis, the first cosmological results from the combination of large-scale structure and weak gravitational lensing, and pioneering studies with cosmic voids. Beyond DES, I also spend time developing and applying new inference techniques that enable a principled and Bayesian analysis of galaxy survey data, including the modeling and characterization of their limiting systematic effects, and I have recently published a number of essential analyses on those lines.

Cosmology from the combination of large-scale structure and weak gravitational lensing

Galaxy surveys provide a view of the large-scale structure of the Universe (LSS) by obtaining information about millions of distant galaxies through extensive observation of the night sky. The distribution of galaxies, tracing the large-scale structure (LSS) of the Universe, is related to the total matter distribution, the one carrying cosmological information, but just in a biased way, as galaxies only exist in rather dense dark matter environments. However, the weak gravitational lensing (WL) effect, inducing correlations in the shapes (shear) of distant galaxies due to the presence of gravitational fields between those galaxies and us, is sensitive to the total matter field. Therefore, by combining LSS and WL we can break the degeneracies with the galaxy bias and access the cosmological information contained in the growth of cosmic structures and the local expansion rate.

The main large-scale structure and weak lensing observables are the correlation functions of galaxy clustering (galaxy-galaxy), galaxy-galaxy lensing (galaxy-shear) and cosmic shear (shear-shear). For the DES Science Verification (SV) data, in Kwan, Sánchez et al. (2017) I measured the angular clustering and the galaxy-galaxy lensing of red galaxies in the DES-SV data and co-led the first cosmological analysis from the combination of LSS and WL probes in DES. This combination of clustering and galaxy-galaxy lensing breaks the degeneracies between cosmological parameters and galaxy bias, which we also studied in detail in Prat, Sánchez et al. (2018a).

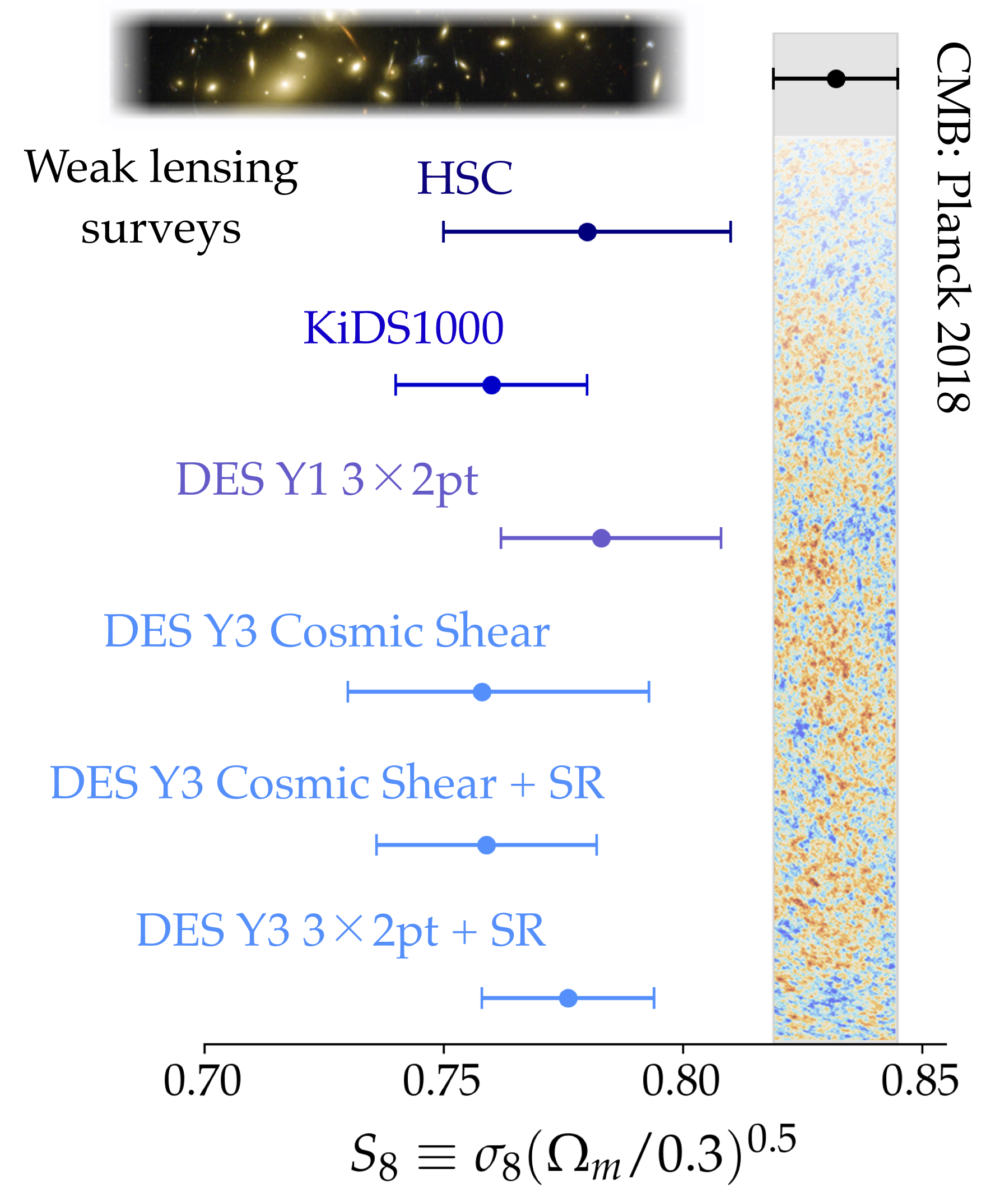

The analysis of the DES Year 1 (Y1) data set used a more optimal extraction of cosmological information, involving the full combination of the three two-point functions, in what is now the standard in the field, and refered to as a 3x2pt analysis (Abbott et al. 2018). This combination not only maximizes the information but also helps in constraining systematic effects that influence each probe differently. For that analysis, I co-led the measurement and characterization of one of the three correlation functions, galaxy- galaxy lensing (Prat, Sánchez et al. 2018b). In that work, we provided what it is one of the highest signal-to-noise weak lensing measurement to date, with S/N = 73, and the full DES Y1 3x2pt cosmological analysis that we performed using those three probes demonstrated comparable constraining power to that from the Planck CMB analysis (see the figure on the right, showing the constraints by various surveys and the CMB on the amplitude of matter fluctuations and the matter density in the Universe).

We recently released the cosmological analysis of the DES Year 3 data sample, which included around 30 different publications. The results were presented to the communnity in a live webinar in front of more than 700 people (I was one of the speakers in the webinar).

Characterizing Photometric Redshifts

Extracting cosmological information from imaging surveys requires the estimation and char- acterization of the redshift distributions of galaxy samples using broadband photometry. Critically, with the increase of statistical power as current and especially future photometric surveys collect more data, the systematic errors from redshift mis-calibration constitute one of the most important roadblocks to access cosmological information and to reveal the nature of dark energy. During my carrer I have lead a number of crucial publications that granted me a world-leading role in the field of photometric redshift characterization.

In Sánchez et al. (2014) I led the first assessment of the photometric redshift (photo-z) capabilities of the DES Camera, which was the world’s most powerful digital camera at the time. We characterized an extensive set of photo-z algorithms, including state-of-the-art machine learning techniques, and my work enabled the subsequent state-of-the-art science carried out by DES, also becoming a central reference in the photo-z literature.

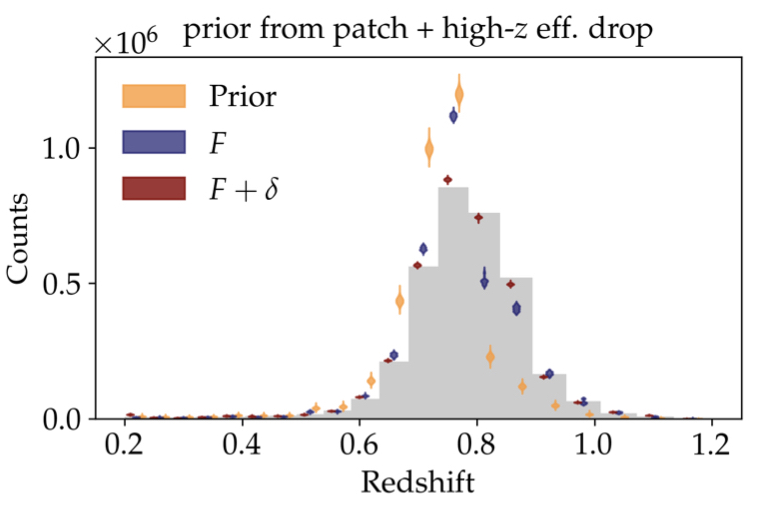

Subsequently, in the DES Year 1 cosmological analysis, the redshift calibration of source galaxy populations used a combination of prior, high quality, redshift information from the COSMOS field, DES photometry, and the clustering against a population of galaxies with precise redshifts. However, the combination of these sources of information is not trivial, and was only performed on a single summary statistic of the redshift distribution, its mean. More recently, I have developed a method which allows to combine, for the first time, in a principled and Bayesian way, galaxy clustering, photometric, and spectroscopic information into a single redshift distribution inference (Sánchez & Bernstein 2019). The method uses a hierarchical Bayesian model which provides full posterior distributions on those redshift probability distributions, enabling the full propagation of redshift uncertainties into cosmological analyses while using all the information at hand to reduce those uncertainties and associated potential biases. Afterwards, in Alarcon, Sánchez et al. (2020), we tested the method in realistic N-body simulations, developing key extensions on the treatment of galaxy clustering. Even in cases where we artificially bias the spectroscopic sample to induce a shift in mean redshift of order 0.05, the final biases in the posterior are 0.003 or smaller (see the figure 1 on the right). This robustness to flaws in the redshift prior or training samples would constitute a milestone for the control of redshift systematic uncertainties in future weak lensing analyses.

Furthermore, in Sánchez et al. (2020), I studied the effects of sample variance introduced by large-scale structures in redshift priors. Given the small size of spectroscopic or high-quality photometric redshift calibration data sets, this is one of the leading systematic uncertainties. Crucially, I developed a new sampling method and the corresponding theoretical framework to enable the full propagation of these uncertainties into cosmological inference.

These methods constitute the state-of-the-art in the field, and they form the basis of the redshift calibration in the DES Year 3 cosmological analysis, in which I played a leading role as the co-lead of the Redshifts Working Group in DES. For that analysis, which is one of the most ambitious weak lensing analysis to date (with more than 100 million galaxies in the source sample), we are for the first time marginalizing over redshift uncertainties using full realizations of redshift distributions (not only mean redshift shifts), sampled using the method in Sánchez et al. (2020), and we are combining photometric information with galaxy clustering and lensing (shear) ratios (SR), as described in Sánchez, Prat et al. (2021).

Cosmic voids and void lensing

Cosmic voids are large, nearly empty regions in space surrounded by a filamentary network of galaxies and dark matter. Due to their low matter density, voids are extremely sensi- tive to diffuse components such as dark energy, and hence represent ideal entities to study modifications of gravity, and also provide independent and complementary information to galaxy-based studies. However, no void studies existed for imaging surveys given the difficulty of detecting them due to photometric redshift errors. That situation changed when in Sánchez et al. (2017) I developed a novel void finder designed for minimizing the impact of such errors, and I successfully performed the first measurement of void lensing in a photometric survey. In the animation on the right, one can see the relation between the galaxy density field (smooth red), galaxy clusters (solid black points) and cosmic voids (open circles) from redshift z=0.2 to z=0.8 (more than 4 thousand million years!) in the DES-SV footprint, using the set of voids I determined in that work.

Importantly, that study constitutes a milestone for void science, as it unlocks void analyses from the huge amount of data coming from imaging surveys. As an example, the void finder I developed has later been used to analyze the late-time Integrated Sachs-Wolfe effect via the CMB imprint in voids (Kovács, Sánchez et al. 2017,2019), an effect which has presented excess signals in the past (Granett et al. 2008). Furthermore, as another example, the void finder has also been used to trace the relationship between mass and light in void environments (Fang et al. 2019).